The Impact Of The C.M.S. On The History Of Idumuje-Ugboko

In the years between 1897 and 1902, the bucolic town of Idumuje-Ugboko was already well-established, structured, thriving and relatively peaceful. Traditional religious worship was prevalent. Subsistence farming, the mainstay of the community flourished. However, there was little else in terms of education, modernity or sustained contact with the ‘outside world’. In contrast, England was described by Frances Hensley in the Niger Dawn as a society that was ”gay and lovely with signs of prosperity, peace and plenty on every hand”. Despite the apparent comfort and prosperity, and hot on the heels of the abolition of the slave trade, a quiet but pious evangelical movement was taking root. The movement was led by the intrepid and selfless men and women of the Church Missionary Society (C.M.S.). Spurred on by the clarion call to spread the Christian message and beam the searchlight on what was then considered a benighted part of the world, these two completely, dissimilar worlds were about to collide. Unbeknown to these rural people, their society and the way they lived was not going to be the same again.

According to Frances Hensley’s account in the Niger Dawn, the first party of the C.M.S. missionaries arrived at Idumuje-Ugboko from Asaba on 8, January 1902. She writes: ”we entered the town of Idumuje by a wide avenue of trees. Abraham, the teacher met us here, with the king and his uncle [Odor], and we were led in state to Abraham’s house, and given a nice inner room to ourselves”. By all accounts, Frances and her party which included Miss E.A.Warner and Miss Ellen Dennis were accorded a snug welcome by Omoruhusi and his uncle. She further stated:

In this section, the primary focus will be on the activities of the C.M.S. in Idumuje-Ugboko particularly, the role played by Frances M Hensley and the profound effects their arrival had on the community in general and the monarchy in particular. In segments, we will look at the influence of the C.M.S. on:

- The reign of Omorhusi

- The pre and teen years of Obi Nkeze Nwoko II and

- Ani-Ofu

The Mission Activities During The Reign Of Omorhusi

The arrival of the C.M.S. in Idumuje-Ugboko heralded the opening up of the community to the outside world, especially the exposure to Christianity and the British colonial rule. Even though Omorhusi was the custodian and a worshipper of traditional religion, church services were held in a section of his palace in the early part of 1902. Later that year, and upon a request, a virgin portion of land was bequeathed to the C.M.S. by Omorhusi. Probably uninhabited, this stretch of land was called Ani-Ofu (New Land). One of the reasons why this patch of land was chosen was because of the easy access to the legendary and the pristine streams the community was blessed with, particularly, Iyi Ugo. In fact, Idumuje-Ugboko was singled out as a suitable headquarters of the C.M.S. West of the Niger because of the congenial surroundings and the presence of these streams. In her book Niger Dawn, Frances Hensley writes:

The arrival of the C.M.S. in Idumuje-Ugboko heralded the opening up of the community to the outside world, especially the exposure to Christianity and the British colonial rule. Even though Omorhusi was the custodian and a worshipper of traditional religion, church services were held in a section of his palace in the early part of 1902. Later that year, and upon a request, a virgin portion of land was bequeathed to the C.M.S. by Omorhusi. Probably uninhabited, this stretch of land was called Ani-Ofu (New Land). One of the reasons why this patch of land was chosen was because of the easy access to the legendary and the pristine streams the community was blessed with, particularly, Iyi Ugo. In fact, Idumuje-Ugboko was singled out as a suitable headquarters of the C.M.S. West of the Niger because of the congenial surroundings and the presence of these streams. In her book Niger Dawn, Frances Hensley writes:

It is on record that during the C.M.S. itinerations, potable water was ferried from Idumuje-Ugboko to towns as far as Obior, Umunede, Agbor, Igbodo and other adjoining communities. Frances Hensley writes:

As the evangelical work in Idumuje-Ugboko and the nearby towns and villages steamed ahead, people began to discard their idols. In Idumuje-Ugboko, the Odogwu, chief Esenanjo was the first chief to discard his idols. Esenanjo’s family background is also a testament to Obi Omorhusi’s non-nativist approach to governance. Esenanjo was born to an Idumuje-Unor father, Mafiana of Ogbe-Akwu village. His mother was Mgbakor from Ogbe-Ofu quarters in Idumuje-Ugboko. Upon losing his father at a very young age, his mother relocated the family to Idumuje-Ugboko and settled in Idumu Obu. Over a while, he rose to prominence and importance. In his prime, he was not only the Odogwu but also a representative on the native council in Issele-Uku and a tax collector in Idumuje-Ugboko.

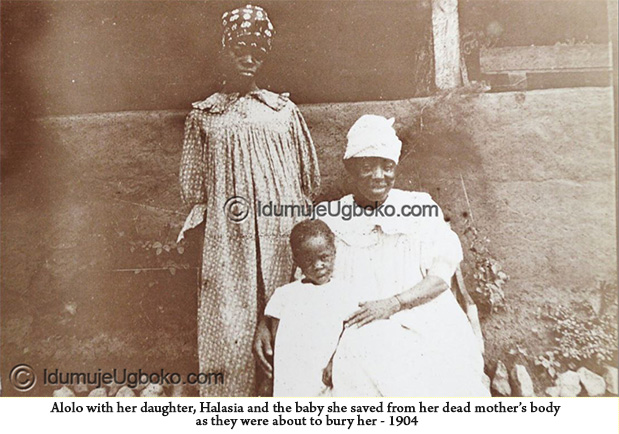

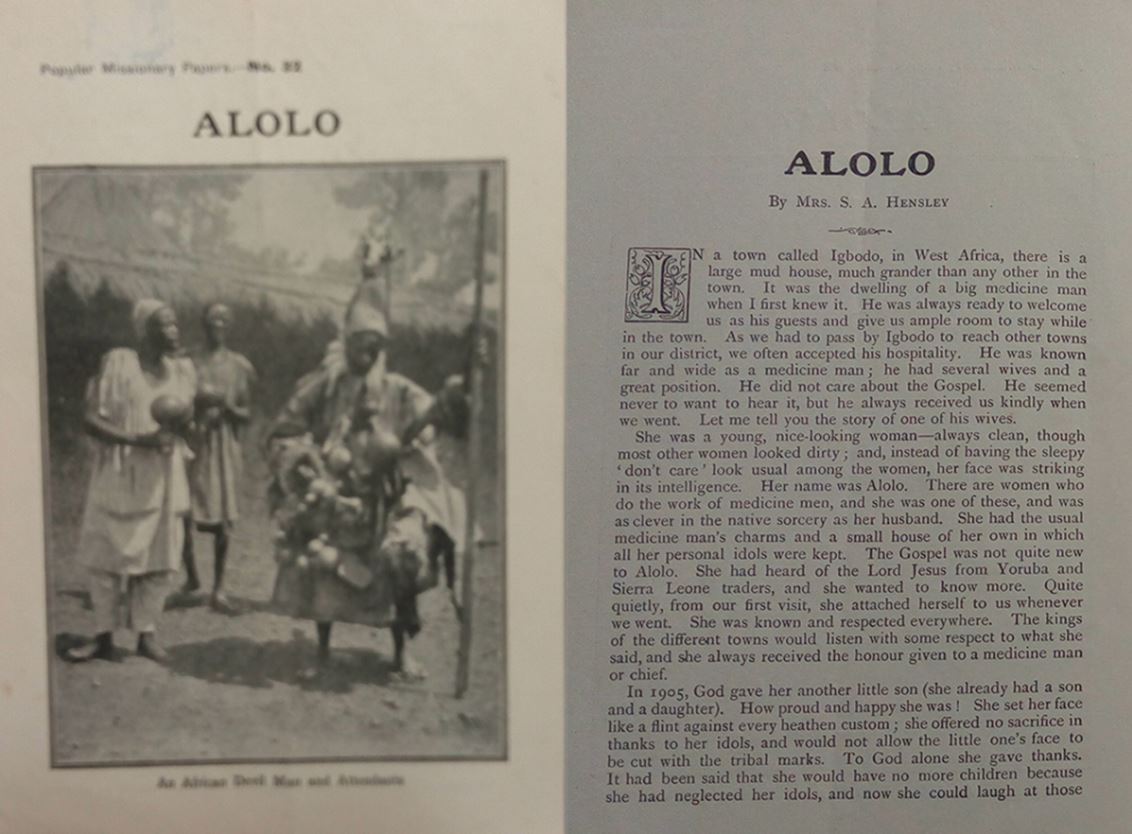

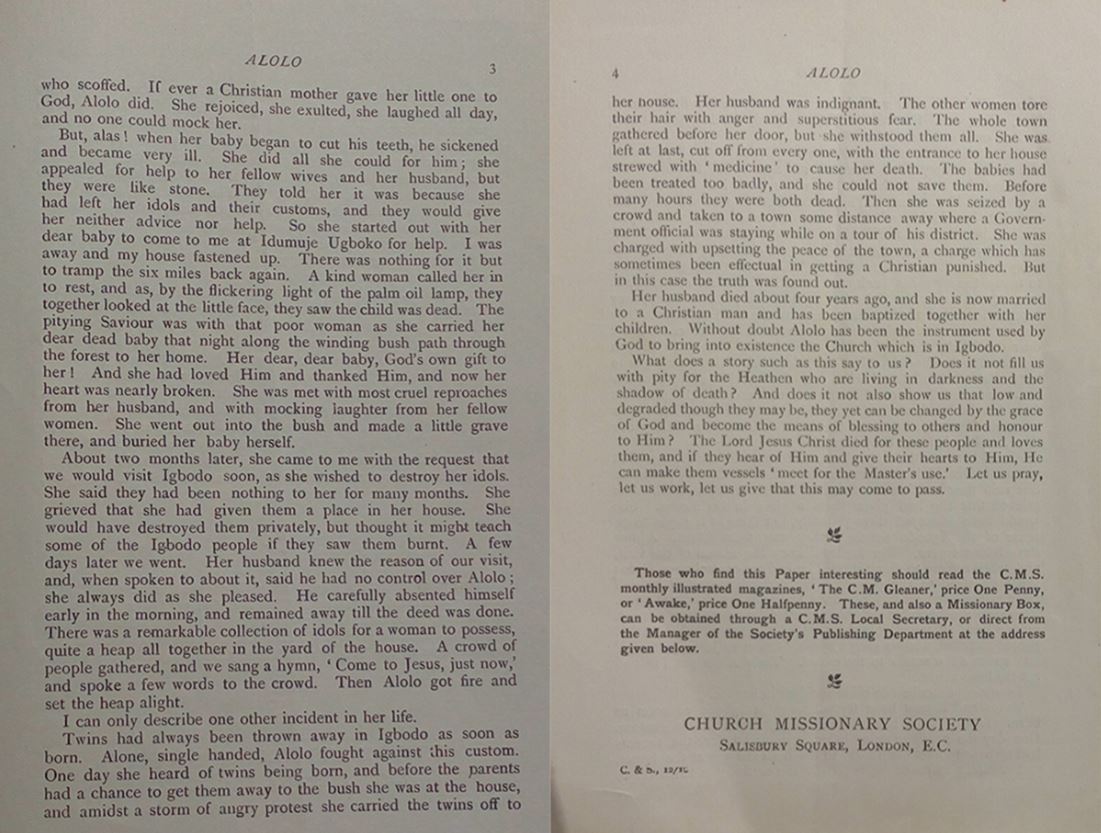

In Igbodo, Alolo who would later become an inspiration to many was the first Igbodo Christian convert to destroy her idols, an occasion which was described as momentous by Frances Hensley. She writes:

In the early days, the C.M.S. proselytizing resulted in thirty men and four females in Idumuje-Ugboko turning their back on the prevalent traditional religious worship to become Christians. Over a short period of time, the number of catechumens who attended the night school grew from strength to strength. By 1904, four Idumuje-Ugboko girls were already being educated at Onitsha Girls School.

Despite the expected resistance from the worshipers and the custodians of the various shrines, the Christian message was surprisingly well-received in Idumuje-Ugboko. Frances Hensley writes:

The new converts began to see the folly of trusting in inanimate objects and started to discard them. Some even learned to read and write in Ibo. Frances Hensley writes:

Having tried and failed to convert to Christianity in April 1903, in June of the same year, Omorhusi finally destroyed his many idols. Some Christian women converts from Asaba came to witness the unusual spectacle of a King actually destroying his idols. Frances Hensley writes:

Further, Omorhusi started taking baptismal lessons. France Hensley writes:

On Sunday, March 1, 1903, an Ogbe-Ofu boy Adigwe was accidentally killed by another boy at the village stream. According to the custom of the land, the murderer was expected to either take his own life or be hanged. Despite the plea for clemency by some chiefs, notably Esenanjo (the Odogwu) and Ogwu (the Iyase), the culprit was summarily hanged. Even though the chiefs and some elements within the community tried to argue that it was the law of the land, the colonial government was having none of it. In the eyes of the new colonial law, this was a premeditated murder. This led to the arrest of the individuals who carried out the hanging and two chiefs, Uche and Eyè as principal witnesses who superintended the killing. As head of the kingdom, Omorhusi was also compelled to appear as a witness before the DC (Divisional Commissioner) at Asaba. Inexplicably, Uche and Eyè were found not guilty due to lack of sufficient evidence as most of the witnesses did not truthfully testify to their role in the killing. However, other suspects were tried, found guilty and imprisoned for 3 months in Asaba for the murder. Frances Hensley stated:

By all accounts, Omorhusi was prepared to hire a personal teacher to facilitate his conversion and tutor him on how to read and write in the Ibo language.

In her chronicle, one of the early converts in Idumuje-Ugboko was one of Omorhusi’s wives named Chijiokwu, baptised Lois. Following the pillaging of Idumuje-Ugboko by the Ekumekwu fighters, Chijiokwu found herself taking refuge in her hometown of Igbodo. Amidst the unrest and the confusion that followed the murder of the District Commissioner Mr Crewe Read at Owa near Agbor on June 10, 1906, the colonial government dispatched security operatives to quell the unrest. Without waiting to properly identify them, the natives thought the operatives were the dreaded Ekumekwu fighters. Fearing the worse, her people made a beeline for the surrounding bushes. Unperturbed by the confusion and the noise made by their guns together with the unbearable pain on her injured foot, Chijiokwu stood her ground and expressed herself in the little English she knew. Holding her arms up she called out:

Her ability to communicate clearly and profess her faith may have saved this woman and her little child from the wrath of the government representatives.

Sadly, this period of steady C.M.S. evangelical outreach was interrupted by the first Ekumekwu uprising. The Ekumekwu, meaning ‘not speaking’ war was orchestrated by a wide section of the Anioma irredentists and cultists. They saw the missionaries and the converts as unwelcome representatives of the imperialist British government, sent to take over their land, lord it over them and completely change their way of life. In fact, any native who converted to Christianity was branded a quisling. Although the uprising engulfed the majority of the Anioma region, Idumuje-Ugboko was disproportionately affected by the Ekumekwu ‘wrecking ball’. The desecration of the objects of worship, the total destruction of the first Saint Emmanuel Church and the first Women’s Institute in the Ibo hinterland were collateral evidence of the uprising. Unfortunately, the war necessitated the first evacuation of the C.M.S. from Idumuje-Ugboko resulting in a chasm in mission work although, for a very short period. The subjugation of the unrest saw the ringleaders and their associates were mostly incarcerated. Some notable figures in Idumuje-Ugboko were imprisoned. Nwabuokei of the royal family and one of the ring leaders of the Ekwumekwu was imprisoned in Asaba for six-months. He died on Sunday, June 14, 1903, a day before he was due to be released.

As calm returned at the end of the first Ekumekwu storm, the C.M.S. and Frances Hensley were graciously invited back to Idumuje-Ugboko by Omorhusi. Omorhusi further cemented his reputation as a moderniser by supervising the rebuilding of all the mission facilities that were destroyed by the Ekumekwu war. Although the C.M.S. continued to enjoy the unequivocal support of Omorhusi, their second coming proved more challenging in more ways than one. This period coincided with the subtle but firm confrontation of certain social practices and traditions that were loathsome to the Christian faith. Some of these practices included polygamy, (child) betrothal, forced marriage, tribal or idol dedication marks (cicatrisation), the killing of twins as well as a peculiar type of infanticide associated with teething in children.

Two types of killings, in particular, drew the ire of the missionaries and the colonial government – the killing of twins and the killing of any baby who, at the teething stage, was unfortunate to present a set of upper teeth or tooth. The presence of twins or the cutting of the top tooth or teeth was seen in most Ibo towns and villages as a foreboding, capable of annoying the gods and inflicting an imprecise hardship on the community. In both instances, the children were immediately thrown into the ‘bad bush’ to die a very slow and excruciating death. To avert this illusory presage of adversity, the children must, even against the will or the protestation of their mothers, be deposited in the ‘bad bush’. In extreme circumstances, a nursing mother of twins may be ostracised or completely banished from her community.

Two types of killings, in particular, drew the ire of the missionaries and the colonial government – the killing of twins and the killing of any baby who, at the teething stage, was unfortunate to present a set of upper teeth or tooth. The presence of twins or the cutting of the top tooth or teeth was seen in most Ibo towns and villages as a foreboding, capable of annoying the gods and inflicting an imprecise hardship on the community. In both instances, the children were immediately thrown into the ‘bad bush’ to die a very slow and excruciating death. To avert this illusory presage of adversity, the children must, even against the will or the protestation of their mothers, be deposited in the ‘bad bush’. In extreme circumstances, a nursing mother of twins may be ostracised or completely banished from her community.

The efforts made by the C.M.S. to stamp out this obnoxious practice was succinctly captured by Frances Hensley in one of her letters. She writes:

When the practice of forced marriage was outlawed by the colonial government, there was a palpable feeling of indignation among the locals. The menfolks who reveled in marrying many wives kicked out against this new law, sometimes violently resisted it. They saw everything the missionaries stood for as foreign and prescriptive. In essence, they wanted to maintain the status quo. On the other hand, to the young men who found it increasingly challenging to find a wife, and a sizeable number of nubile girls who dreaded being forced into matrimony, the new law and its enforcement by the government through the missionaries was a welcomed relieve.

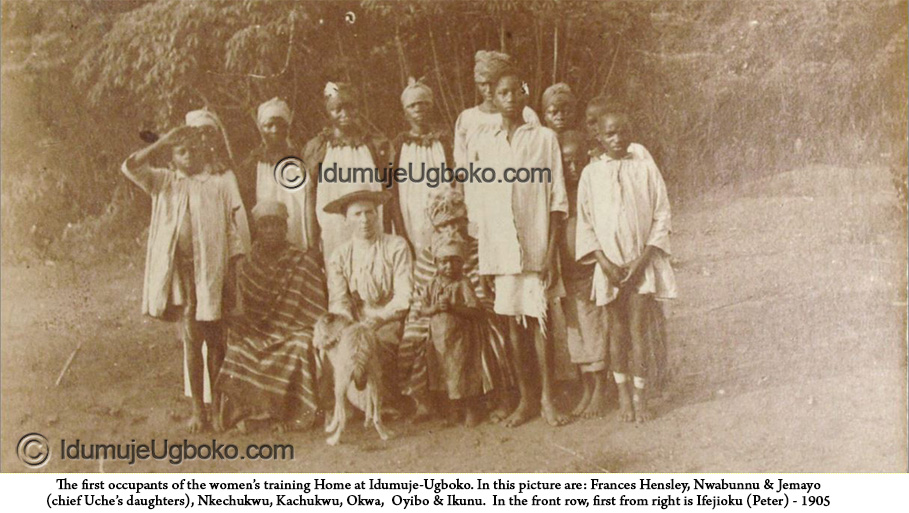

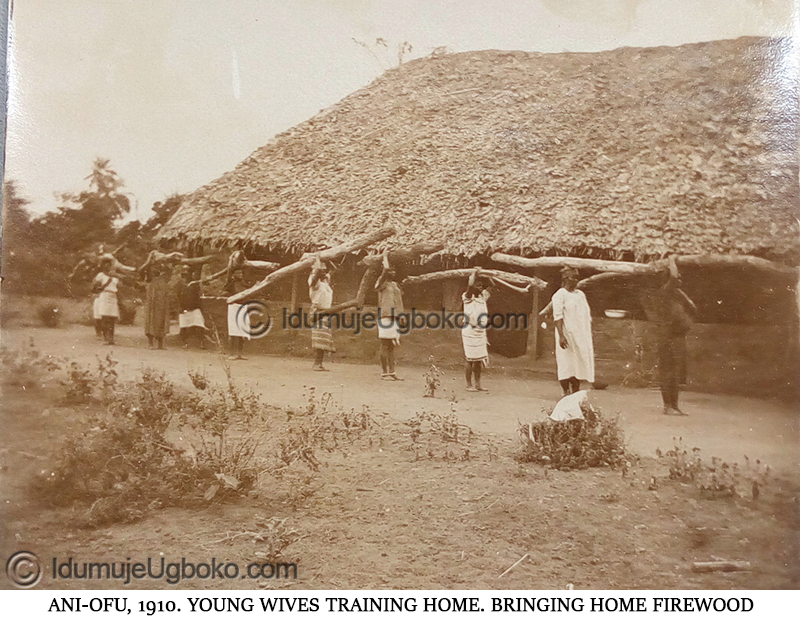

One of the direct consequences of this change in law was the founding of the first Wives Training Home in Ani-Ofu, Idumuje-Ugboko, the first of its kind in Nigeria. The establishment of this home encouraged the schooling of young girls in the Bible. The home also doubled as a centre for education where the girls were taught how to read and write in the Ibo language. It also acted as a place of refuge for the girls and the women who converted to Christianity and turned their back on the practice of betrothal and the suffocating tradition of forced marriage.

For the girls already betrothed and a bride price paid and accepted, their prospective husbands had to pay back the bride price before the girls were allowed to marry them. Frances Hensley writes:

Tellingly, despite being the chief custodian of the culture and the tradition of his kingdom, Omorhusi’s 14-year-old sister Mumezia, baptised Mary, was the first young lady in Idumuje-Ugboko to be set free from the bondage of betrothal, and the first native to attend the girls’ school at Onitsha. After her education, she got married to David Eze (full name -Eze dim azu), the first Christian convert from Umunede; the same day John Elumelu Nwoko (Alfred Nwoko’s father) got married to Ogwu’s daughter, Ashiedu, baptised Minnie. Ashiedu was Onwadiegbo’s younger sister and Alfred Nwoko’s mother. Frances writes:

…. His will be the first Christian marriage in Ugboko and we hope will cause great interest. They all know the bride as she is the sister of the king and she has been in the girls’ school nearly three years.- Frances Hensley

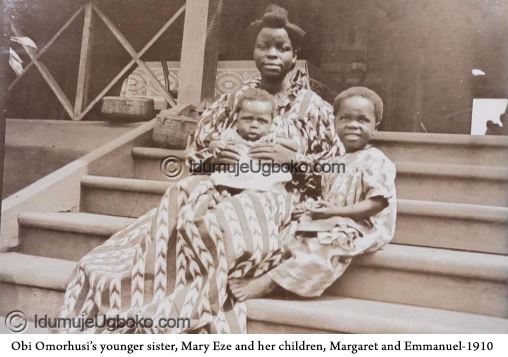

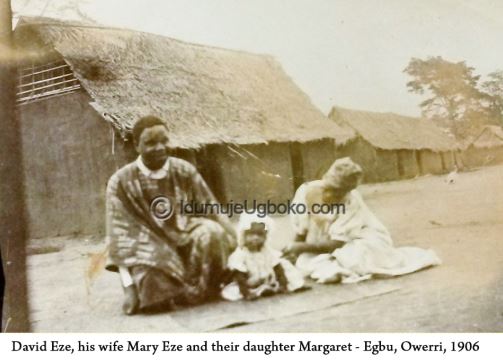

The social and spiritual welfare of the male converts together with their education was not ignored. Some male converts like John Elumelu Nwoko (the first Idumuje-Ugboko male convert and Obi Omurhusi’s younger brother), David Eze (first Umunede male convert), Rufus Ayanna, Paul Odega Monye (Otenu’s father and Obi Omorhusi’s cousin), Philip Iyese (from Ugboko), David Juweh (from Ugboko), Jide (from Idumuje-Unor), Aaron Honnah (from Ugboko), John Mmajuonye (from Obomnkpa), Samuel Egoaza [Diai] (from Ugboko), Joshua Jibunor (from Akwukwu-Igbo) and Jacob all of whom passed through the Boys’ House in Idumuje-Ugboko, applied and were accepted as C.M.S. evangelists. Much later, these young men led various church ministries East of the Niger. Ayanna was stationed in Nnewi, while David Eze, together with his wife Mary Eze worked extensively with Tom Dennis and Frances Hensley at Ebu (Egbu), near Owerri.

Sadly, David Eze, the first male convert from Umunede died on Sunday, August 22, 1909, in Idumuje-Ugboko and was buried there. Prior to being widowed, Mary Eze and David Eze had a son (born on 17 October 1908 in Emi, Imo State) and a daughter, Margaret. Margaret Eze (Frances’s goddaughter) later married a clergyman, Reverend Okwuadi from Igbodo. Together, they had eight children. Up until the late 1940s, Mary and her husband were stationed at the parish and district of Ogwa in the present-day Imo state.

In one of her last letters when she got back to England, Frances crystallised the firm confrontation of certain anachronistic customs by the C.M.S. She writes:

John Mmajuonye’s wife died at Owerri in June. You remember he is the man who was a medicine man of great note in the Idumuje District before he became a Christian. – Frances Hensley

Unlike many traditional rulers of his time, Omorhusi bucked the trend by not only providing a soft landing for the early missionaries. He went a step further by giving his eldest son Nkeze to be nurtured and educated by the missionaries. This was vividly captured in one of Frances Hensley’s letters. She writes:

Nkeze is the eldest son of the king of Idumuje and has been given to me to train so that when his father dies & he becomes the king he may be a good king for them. He is about six. Mrs Hornby has been keeping him for me while I was away at home.

–Frances Hensley

Undoubtedly, the early success of the C.M.S. in Idumuje-Ugboko and the surrounding villages owed a lot to Omorhusi’s munificent gift of Ani-Ofu, his open-door policy and the benign atmosphere that characterised his reign. As early as June 1903, Frances Hensley appropriately put it this way:

One particular entry validates Omorhusi’s positive disposition towards the missionaries. Frances Hensley writes:

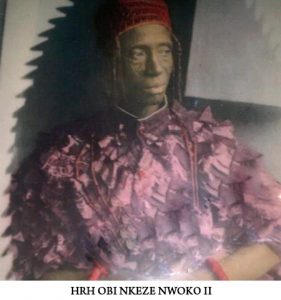

By the time he died on January 23, 1928, his son Nkeze Nwoko II was sufficiently educated (a rarity at that time), his kingdom unsurprisingly peaceful and well-placed to maximise the gains brought about by the coming of the C.M.S.

It is therefore safe to conclude that historians have either deliberately and inexplicably downplayed the significance of Omoruhsi’s kingship, or they are just slowly beginning to recognise the building blocks his meritorious reign bequeathed the town of Idumuje-Ugboko. Understandably, the education, the well-documented reign and the undeniable achievements of his son Obi Nkeze continue to cast a long shadow over Omorhusi’s glorious and exemplary leadership. However, thanks to this assignment, his incontestable accomplishments and the indelible footprints his unexampled rule left on the sands of time are just beginning to come to light. This in turn makes it impossible to airbrush Omorhusi from the history of Idumuje-Ugboko in general and the Nwoko ruling family in particular. Consequently, it will not be ill-considered but fully merited, if a portion on his epitaph is rewritten to read, … And He Was A Consummate Visionary.

The Impact Of The C.M.S. On The Early Life Of Nkeze Nwoko II

Although other denominations like the Baptist and the Roman Catholic churches were rooted in most parts of the Ibo communities by the middle of the 20th century, the impact of the C.M.S. in general and Frances M Hensley in particular cannot be overemphasised. To fully understand how important their arrival was in the formative years of Nkeze, let us take a historical walk to 1895, Nkeze’s year of birth.

Although other denominations like the Baptist and the Roman Catholic churches were rooted in most parts of the Ibo communities by the middle of the 20th century, the impact of the C.M.S. in general and Frances M Hensley in particular cannot be overemphasised. To fully understand how important their arrival was in the formative years of Nkeze, let us take a historical walk to 1895, Nkeze’s year of birth.

Following the death of his father Amoje and through the quaint tradition of Igbu Na Nzo or widow inheritance, a young Omorhusi married his father’s widow, Onwughai. Together, they had two children, Nkeze and Nwobe.

Even though Omorhusi was uneducated and an unbeliever, he probably decided against the advice of the palace advisers to ‘give away’ the crown Prince Nkeze to Frances Hensley, a C.M.S. missionary, aged seven. As his first son and heir to the throne, two possible reasons may have informed his decision. First, and most probable, Omorhusi inexplicably had the foresight to recognise this new and foreign religion as an ’empowerment’ tool for his son. Admittedly, how he figured this out is difficult to comprehend. Second, but highly unlikely, circumscribed by the quainter custom that forbade an heir from sleeping under the same roof as his father, Omorhusi’s hands may have been forced to give Nkeze away in order to conform to this tradition.

Whatever the reasons, now in Frances Hensley’s care, a young Nkeze, together with other converts, notably Uwaje of the Umunede royal family, Eluemenan, a royal from Igbodo, and Ide of the Obior royal house evangelised with the C.M.S. for more than two decades. Getting them ready for an outreach visit to Obior, Frances writes:

Whatever the reasons, now in Frances Hensley’s care, a young Nkeze, together with other converts, notably Uwaje of the Umunede royal family, Eluemenan, a royal from Igbodo, and Ide of the Obior royal house evangelised with the C.M.S. for more than two decades. Getting them ready for an outreach visit to Obior, Frances writes:

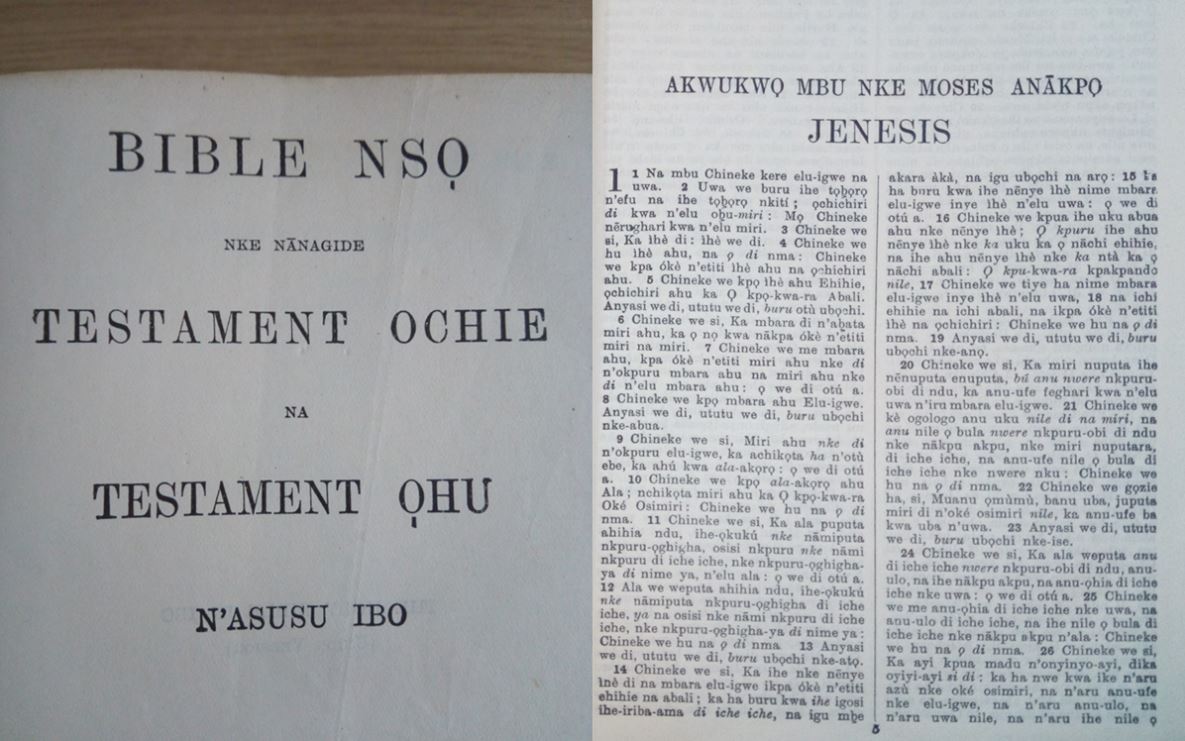

The mission work took them as far as Ebu (Egbu), near Owerri. This is significant because this was where the first complete Ibo Union Bible was co-written by Thomas Dennis, Frances’s elder brother, who remains immortalised by having the renowned Dennis Memorial Grammar School Onitsha named after him. Under the guidance of Frances Hensley, the teenage Nkeze was unrelenting in spreading the Christian faith.

Fueled by the discontent felt by the locals against the chiefs and the royals, the resurgence of the Ekumekwu war precipitated the second and final evacuation of Frances M Hensley and a coterie of staff and helpers from Idumuje-Ugboko. Crucially, this unfortunate situation signaled the shift of base, activities, and personnel from Idumuje-Ugboko to the Eastern side of the river Niger.

In spite of the inauspicious end to the C.M.S. activities in Idumuje-Ugboko and the tearful parting of ways with Frances Hensley at the banks of the River Niger, Nkezi aged fourteen was put into the care of Miss Hornby at Iyienu. As far as Nkeze was concerned, it was not all about evangelism. He seized the opportunity to acquire Western education. He succeeded in gaining a grade II certificate from the Teacher Training Institute at Awka. He later worked for five years as a court interpreter before ascending the throne in 1928.

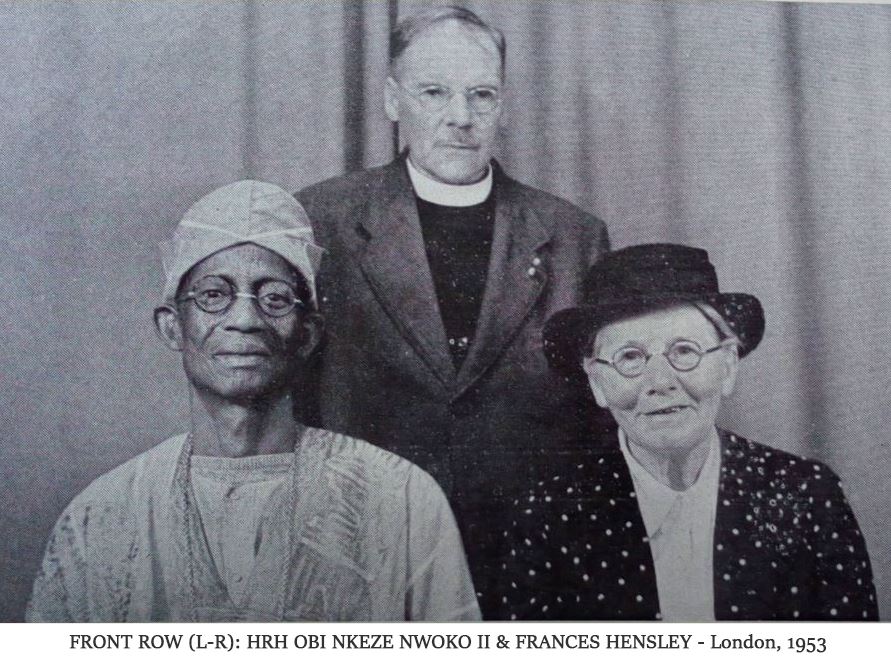

Fate was to reunite Nkeze Nwoko II with Frances Hensley in August 1953. The fortuitous meeting came about when Obi Nkeze was nominated by his peers in the delegation of traditional rulers to the pre-independence conference in London. Nkeze, now a grown man and the Obi of Idumuje-Ugboko was not about to forget the pivotal role played by Frances Hensley in his formative years. For example, when she was stationed at Idumuje-Ugboko, Frances described her intervention in nursing back to health a very sick Nkeze. France writes:

Fate was to reunite Nkeze Nwoko II with Frances Hensley in August 1953. The fortuitous meeting came about when Obi Nkeze was nominated by his peers in the delegation of traditional rulers to the pre-independence conference in London. Nkeze, now a grown man and the Obi of Idumuje-Ugboko was not about to forget the pivotal role played by Frances Hensley in his formative years. For example, when she was stationed at Idumuje-Ugboko, Frances described her intervention in nursing back to health a very sick Nkeze. France writes:

Fondly referred to as ‘mai‘ – a shortened form of ‘mma anyi‘ (our mother) by Obi Nkeze and her other charges, Nkezi wasted no time in seeking her out through the C.M.S. office in London. That chance meeting was affectionately captured in the Sequel of the Niger Dawn. See picture above.

Furthermore, on one occasion, Frances ensured Nkeze was shielded from a custom she reasoned was at odds with his fledgling Christian faith. Thus, when Iyebor Onwughai’s mum and Nkeze’s maternal grandmother died on May 9, 1903, the brief description of the activities surrounding her burial the following day is a testament to Frances looking out for Nkeze in more ways than one. Frances Hensley writes:

Through his association with the C.M.S. and Frances Hensley in particular, Nkeze was able to add many feathers in his cap. This catapulted him to a rarefied position which some of his contemporaries could only dream of. Some of his achievements include:

- The only educated monarch in and around the old Benin province of the present-day Edo and Delta states – thanks to the grade II certificate he acquired at the teachers training college at Awka in 1924

- A judge of the customary court of Idumuje and Odiani clans

- A district interpreter for five years before ascending the throne in 1928

- A member of the Western House of Chiefs

- Adviser to the Action Group Party at the 1953 pre-independence constitution conference in London

Without his father’s foresight, the arrival of the C.M.S., especially the pivotal role played by Frances Hensley, it is anyone’s guess if Obi Nkeze could have accomplished so much in his relatively short life or be nostalgically remembered as the standout Obi of the Nwoko dynasty. The cynosure of all eyes, his legacies and reign have remained the touchstones of the effectiveness of subsequent Obis in Idumuje-Ugboko. He ruled for 27 years and died in 1955, aged 60.

The C.M.S. In Ani-Ofu

Geographically, Ani-Ofu is located a little further away from the base of Atuma village in Idumuje-Ugboko. For the convenience of classification, Ani-Ofu can be variously described as a village, a (very small) town, or a suburb of a bigger town. Whichever best defines this portion of land, two significant claims are difficult to argue against:

- In the early 20th century and under the third Nwoko dynasty, Ani-Ofu was the administrative headquarters of the Church Missionary Society (C.M.S.) West of the Niger

- The coinage of the word Ani-Ofu almost certainly took place in 1902 during the reign of Omoruhusi

In Frances Hensley’s account in the Niger Dawn, the quest for a ‘pleasant’ land and an uninterrupted supply of clean water played a prominent part in determining where to situate the C.M.S. outpost outside of Asaba. Having identified Idumuje-Ugboko as a good location, the C.M.S. delegation arrived on the evening of 8, January 1902. After settling in, they were given a virgin portion of land by Omorhusi to build a mission headquarter. This area was aptly called Ani-Ofu, meaning New Land.

The C.M.S. built their mission headquarter and the first Young Wives Training home in Ani-Ofu. Over the next eight years, from 1902 to 1910, they conducted most of their mission affairs from here. Using Idumuje-Ugboko/Ani-Ofu as a base, they evangelised, converted, trained and educated the local men and women of Idumuje-Ugboko and the surrounding towns to read, write in the Ibo language and propagate the Christian faith. In her book the Niger Dawn, Frances stated:

Many people have unconvincingly argued that Ani-Ofu predates the C.M.S. Based on historical observations especially the emerging documentation of the C.M.S., this is highly unlikely. However, the writers of this work are of the opinion that before Ani-Ofu became a C.M.S. base, that strip of land that adjoins a section of the present-day Idumuje-Ugboko may have been sparsely populated by itinerant farmers who may have temporarily lived in isolated farm settlements. In fact, some historians claim that before the C.M.S. came, that portion of land was uninhabited and mainly used by Idumuje-Ugboko and Idumuje-Unor indigenes as a farming outpost. However, due to the nature of the settlements, it could not be described as a viable or fully functional hamlet, village or town. It is, therefore, reasonable to assert that the building of the women institute and the mission headquarter may have been the first modern constructions to have taken place in that area. This suggests that the coming of the C.M.S. may have facilitated communal activities in this entirely new and quite possibly, desolate and ‘lifeless’ woodland. According to some commentators it was during or shortly after the C.M.S. nestled in this farming outpost that migrants from Ikoko, Idumuje-Unor, and Idumuje-Ugboko began to permanently settle there.

For many who may argue to the contrary, it is instructive to note that when the C.M.S. wanted a piece of land to build their mission house, they never sought the approval of the Obi of Idumuje-Unor. Instead, it was Omorhusi who identified, approved and supervised the building of the mission house at Ani-Ofu. Also, in her journals, Idumuje-Unor was barely mentioned either as a supervising authority over this new territory. As a result of this ‘casual observation’ and record, there is insufficient evidence to argue to the contrary that, as a community, Ani-Ofu was in existence before the C.M.S arrived. Based entirely on these two related interventions – the coming of the C.M.S and the gift of the land – categorising Ani-Ofu as a separate entity from Idumuje-Ugboko becomes all the more illogical. The question then is, why do the people of Ani-Ofu identify more closely with Idumuje-Unor than Idumuje-Ugboko? Or why do they see themselves as a totally different community from Idumuje-Ugboko?

A believable yet simplistic explanation for the ‘identity crisis’ may be found in the aftermath of the Ekumekwu war. When the C.M.S influence in Ani-Ofu ceased, its close location to a migratory route and the attraction of the lush surroundings may have encouraged a steady and sustained migration from neighbouring villages, especially Idumuje-Unor. Essentially, its geo-position offered not just a convenient ‘landing spot’ for migrants but also a luxuriant environment that fostered the growth of a vibrant community. This, it seems, may account for the shift in demography in favour of Idumuje-Unor, hence the proclivity by some people to regard Ani-Ofu as the fifth village of Idumuje-Unor.

Another valid reason could be the regrettable disconnect between Ani-Ofu and Idumuje-Ugboko, post-Omorhusi. After Omorhusi’s reign, successive Idumuje-Ugboko monarchs never took positive steps to rebuild the ‘physical’ and the ‘cultural’ bridge between the two communities. As a result, Ani-Ofu may have ‘seized’ the opportunity to align herself with Idumuje-Unor while patently disregarding the physical proximity, the historic and the cultural affinities between her and Idumuje-Ugboko. Regrettably, with no discernible efforts at rapprochement, the Ani-Ofu question will remain an existential anomaly.

One thing this exercise is not about is a cue to foment trouble, whip up sentiments or encourage any form of irredentism. Instead, this assignment should be seen for what it is – a genuine interrogation of historical facts that beam the searchlight into those hard-to-reach recesses of our shared history. If this serves no other purpose, it undoubtedly encourages an honest debate which, in turn, may elicit further research into the true status of Ani-Ofu. If this can be achieved, the whole exercise may be viewed as a success.

Ms Alolo of Igbodo

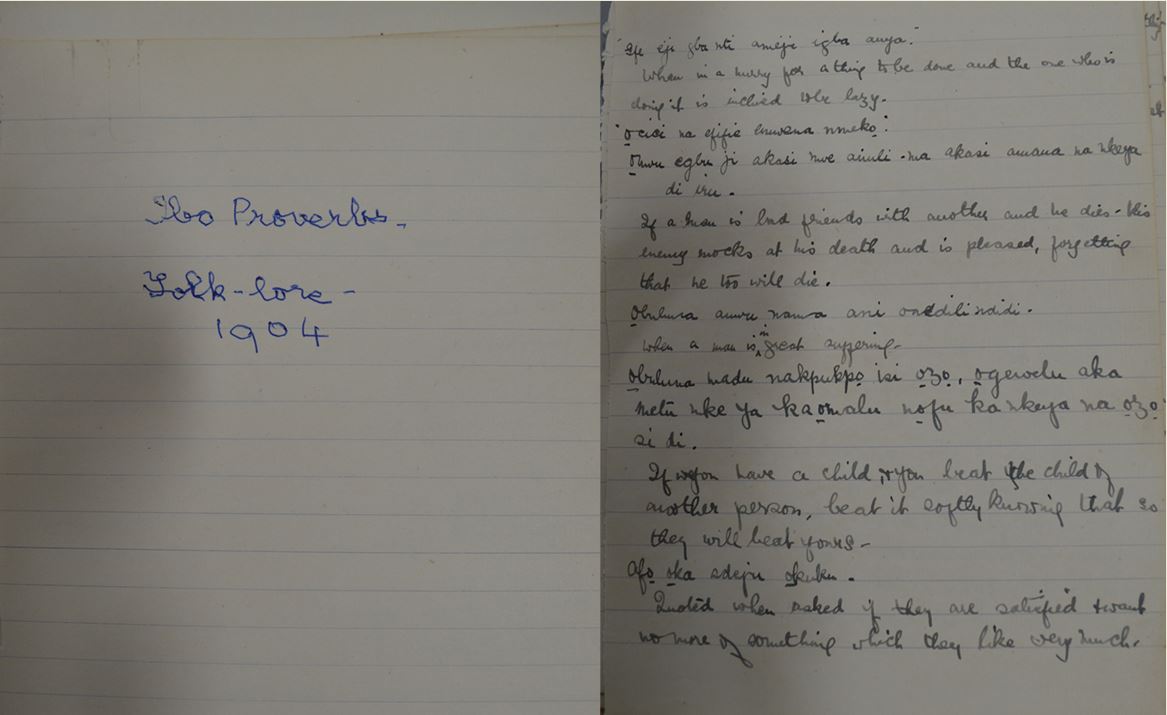

Ibo Proverbs

The Ibo Union Bible Manuscript