The Tradition And The Culture Of Idumuje-Ugboko

Tradition can be defined as the specific modes of thoughts, behavioural patterns or traits found among a group of people which are usually handed down from generation to generation. Culture, on the other hand, is the belief system, institutions, and customs that uniquely differentiate one social group from another. As a homogeneous entity, Idumuje-Ugboko has clearly defined institutions and systems which distinguish and make them who they are.

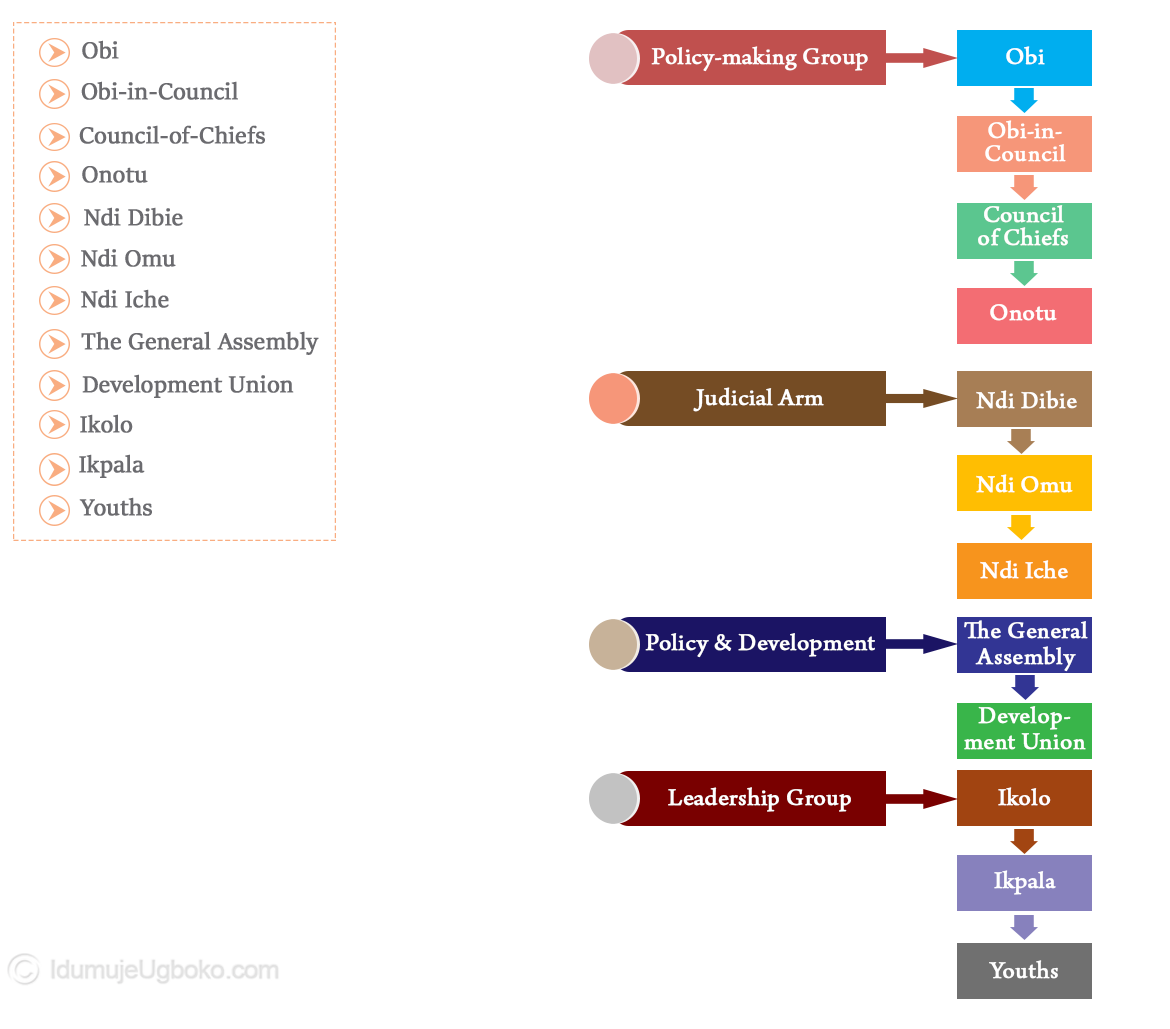

The Hierarchical Social Structure

The social structures in Idumuje-Ugboko have evolved over a period of time. This evolution has played a seamless role in the governance of the community. For the Obi to govern effectively, the various social strata must not exist or function in isolation. Their overall effectiveness acts as a barometer of good governance.

The grouping below is a graphic illustration of the hierarchical social structures and the overarching roles they perform in the community.

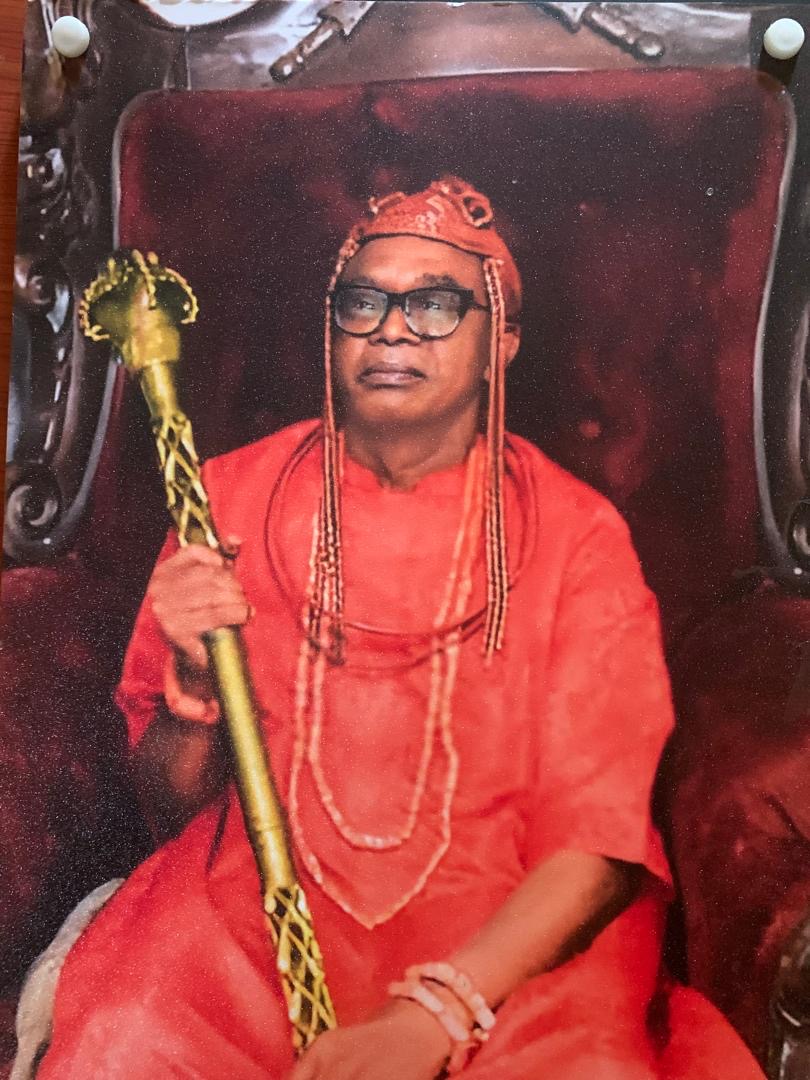

The Obi

Historically, the monarchy in Idumuje-Ugboko is both hereditary and patrilineal. Similar to some monarchies in the Ibo land, the Idumuje-Ugboko system by right of law and custom identify the legitimate, firstborn son to be first in line to inherit his parent’s entire estate (in this instance the throne), to the total exclusion of any younger brothers, illegitimate elder sons, daughters or collateral relatives. This is known as Primogeniture. In practice, it means that the son of a deceased Obi no matter how young is the first in line to ascend the throne before any much older brother of his father. However, if the Obi dies without having a male offspring, his eldest brother is entitled to ascend the throne by the right of substitution.

Historically, the monarchy in Idumuje-Ugboko is both hereditary and patrilineal. Similar to some monarchies in the Ibo land, the Idumuje-Ugboko system by right of law and custom identify the legitimate, firstborn son to be first in line to inherit his parent’s entire estate (in this instance the throne), to the total exclusion of any younger brothers, illegitimate elder sons, daughters or collateral relatives. This is known as Primogeniture. In practice, it means that the son of a deceased Obi no matter how young is the first in line to ascend the throne before any much older brother of his father. However, if the Obi dies without having a male offspring, his eldest brother is entitled to ascend the throne by the right of substitution.

The Obi sits atop the hierarchical structure. Together with the chiefs they are regarded as the custodians of culture, custom, and tradition. He is seen as the chief peacemaker, unifier, arbiter, and by virtue of his office, the spiritual head of the kingdom as well as the chief lawmaker. He governs by putting to good use the different civil institutions, like the Ndi Omu, the Onotu, the Palace Chiefs and the Ndi Dibie. During the reign of Omorhusi, the Ada, the symbol or staff of authority was received in 1924 from the Oba of Benin, Oba Eweka II, the monarch of the old Benin kingdom.

The greeting reserved for the Obi is Obi Agwu, an abridged version of Obi agha agwu na ukpo. Translated but with no word-for-word correspondence, it means ‘The Obi is ever-present on the throne or stool’.

The Obi-in-Council

The Obi-in-Council is the consolidated group of nominated village elders, representatives and the members of two groups of chiefs – the Palace and the Onotu chiefs. The functions of the Obi-in-Council is defined by the four standing committees and the roles they play. The standing committees are:

- The Finance Committee – deals with various monetary matters

- The Land Allocation Committee – oversees the allocation of land, and acts as the community’s land registry

- The Security Committee – superintends the security of the entire community

- The Road Committee – manages and deals with issues concerning roads construction and maintenance

The Council Of Chiefs

The council of chiefs is a composition of all traditional chiefs. It is chaired by the Obi. Their duties include:

- Adjudicating on disagreements between individual chiefs or between the two groups of chiefs – the Palace and the Onotu chiefs

- Hosting visiting dignitaries in conjunction with the Obi

- Setting dates for the various traditional festivals

- Directing and running the town’s general assembly – Izu-Ani

The Ndi Dibie

This group represents the traditional medicine men, euphemistically referred to as the ‘wise men’. They are so characterised because they claim to ‘see and know it all’. They oversee the spiritual needs of the community via divination. There are two distinguishable routes to the membership of this group – Icha Aka and Ibu Aboh. The word ‘Ichaka’ means ‘washing of hands’. According to Idumuje-Ugboko tradition, when a person’s hands are ‘washed’, it helps the individual to identify the secrets of witches and wizards. While ‘Ibu Aboh’ means ‘the carrying of a traditional basket’ containing a cocktail of herbal medicines. Regardless of the chosen route to membership, both processes involve very rigid traditional rites. For the latter, the ceremony lasts approximately four days and is overseen by a group of diviners. It is usually conducted in the open to showcase the putative magical strength of the diviners and the initiates.

As the ‘spiritual wardens’ of the town, the primary functions of this group are as follows:

- To try, convict or acquit anyone accused of witchcraft

- To help identify and deal with anyone accused of poisoning, threatening to harm or actually harming another individual, either physically, or by means of what is commonly referred to as juju or black magic. If an individual is found guilty, appropriate punishment is meted out via divination. This typically involves oath-taking, the presentation of a goat, palm wine and a bottle of liquor to a deity. The greeting for the leader of this group is Oje-Anyegbe

The Ndi Omu

Ndi Omu is a collective name for a group of people (both male and female) who represent and champion the cause of women. The Omu who heads this group must be a woman. She is regarded as the Queen of the group. She is appointed by the Obi following a nomination from Ogbe-Ofu village where the Omu must always come from. The other members of this group are nominated at the village level. The insignia of the Omu is a broom that is usually presented on the assumption of office. This broom must be in her possession at all times. In addition, she Must carry it where ever she goes.

The Ndi Omu, the equivalent of today’s women’s rights group have various unbounded powers. Their responsibilities include:

- Sanctioning anyone who spitefully destroys a woman’s cooking utensils or disrobes a woman during a fight – an act regarded as sacrilegious

- Punishing a woman and a man who have sex in the daytime, either on the farm or in a thicket. This is regarded as a deeply irreverent act that can bring unspecified curses on the culprits in particular and the community in general. If a couple is caught engaging in such an amorous act the Ndi Omu can make the woman and the man dance naked through the length and the breadth of the town with just a snail’s shell and live chicken tied around their waist

- Reconsecrating the entire land if and when such sacrilegious act occurs

- Carrying out acts of divination to ward off bad omens

- Engaging in eye-catching dance displays when important dignitaries visit the palace.

- Managing the village market

The Ndi Iche

This is an age-based group. There are no specific roles reserved for them. Their title and position are largely ceremonial.

The General Assembly (Izu Ani)

The General Assembly or Izu Ani is a representation of all Idumuje-Ugboko adults. The assemblage of this group is usually heralded by the beating of the Ozi (drum), from 04:00 to 05:00. The sounding of the drum is a call sign for all adults to congregate at the palace. Proceedings are usually directed by the palace’s second-in-command. Issues are exhaustively debated and the final decision whispered to the Obi. In turn, the Obi announces the decision to the general assembly. Specific fines are imposed on anyone who goes against the ruling of the assembly or persistently ignores attending the meetings. The Obi is the chair of this body

The Ikpala

This is a small but powerful and influential group of red-cap and white-feather title holders. The day and the year of investiture define seniority in the group. The initiation into the group is usually preceded by oath-taking at a specific shrine.

The custom requires the Ikpalas to set aside three days in a year when they are not allowed to engage in any outdoor activities or go to the farm. During this period, their movements are severely restricted. They are not allowed to go beyond their neighbourhood. The reason is to prevent them from seeing the face of the Obi – an irreverent act. To help them through these three days of strict solemnity, in-laws, friends, and well-wishers send gifts of kola nut, palm wine, food, and firewood to show support and solidarity.

On the third day, the Ikpalas put on immaculately woven white cloth, worn from the waist down, and festooned with neck coral beads and white-feathered red caps. With a carved wooden walking stick called an Osisi – a symbol of authority – the Ikpalas make their way to the palace. A choreographed arrival at the palace signals the end of the ritual. At the gathering, the Obi enjoins the men, the women, and the youth to denounce any evildoer within the town in songs and dance. The leader of the Ikpala is called the Ogene.

The Ikolo

The Ikolo is an all-male leadership group. It is a village-centric group whose leaders are appointed at the village level. Strictly speaking, they have no democratic standing in society. Their leader is called the Okwulegwe. His traditional greeting is Alum.

Once appointed, as long as he is loyal to the village elders and still commands the respect of his fellow Ikolos, the Okwulegwe will remain the head of the Ikolo.

Although lacking democratic status, the Ikolo perform very important duties in the community. These duties are mostly restricted to burial ceremonies – the modern-day equivalent of funeral directors.

Two key responsibilities stand out:

- Grave digging and interment

- The clearing and maintenance of the various village streets

There are strict rules governing the joining, participation or withdrawal from the Ikolo group. Once a member, it is very difficult to disavow the group. A unilateral decision to leave the group is certainly not an option. However, members who are over 40 years can be unanimously excused from the group. That said, there are three recognisable routes to the renunciation of membership. They are:

- Upward social mobility – when a member moves from the Ikolo group to the Ndi Iche group. This can be achieved by taking the Ime Ohai title.

- Sickness or old age induced departure

- A consensus by the entire group to exempt someone whose child or children also belong to the group

In most instances, failure to participate in predetermined manual labour or in grave excavation and interment can attract punitive fines. This can range from a monetary fine to the confiscation of an offender’s property. The property can be domesticated animals or prized personal possessions. Once seized, the items are redeemable upon the full payment of a specified fine.

The Youth

The youth group is made up of both genders whose age range is between 15 to 24 years. Like the Ikolo group, this group is also village-centric.

The youth perform a couple of vital functions in the community. In the main, they:

- Plan and carry out ad hoc and voluntary manual labour

- Periodically put together inter-village debates.

The Development Union

Historically, the Idumuje-Ugboko Development Union (IUDU) was never part of the hierarchical social structure. Nonetheless, it was added to the social structure purely because of its position as a socio-economic enabler by providing funds for infrastructure projects. The structure of the union is such that development funds are usually generated through the annual dues paid by the members at the branch level or via project-specific fundraising initiatives. Often, a portion of the internally generated fund is ring-fenced and remitted to a central body called the National Executive Committee (NEC). The stipulated amount that should be remitted annually to NEC by each branch (home or abroad) is currently fixed at hundred thousand Naira (₦100,000). In principle, it is the duty of this committee to identify, commission and disburse funds in support of pre-agreed projects. Nonetheless, the pooled resource does not preclude the execution of standalone or branch funded infrastructure projects.

The Institutions Of Marriage, Birth, And Burial

Marriage

In most African cultures, the institution of marriage is fundamentally the union of a man and woman. That said, in most liberal societies the sanctity of this institution is currently facing challenges due to the influence of Western cultures and values. Despite these perceived negative influences, the traditional concept of a marriage between a man and a woman still holds strong in most African cultures and will be very difficult to dislodge.

In Idumuje-Ugboko, a marriage is deemed acceptable when it is contracted between a man and a woman from two different Ebos. This extra layer of ‘acceptability’ was put in place to discourage contracting marriages within the same Ebo because such marriages are rightly regarded as a form of inbreeding. The existence of this precautionary measure means that the institution of marriage in Idumuje-Ugboko is, by preference, Exogamous – the custom of marrying outside a close social group, i.e. the Ebo, as opposed to Endogamous – a marriage contracted within the same social group.

Before the advent of Christianity, the culture empowered families mainly fathers to arrange marriages on behalf of their sons and daughters. The lack of resistance from prospective couples and the deference to the culture of the community allowed this awkward arrangement to flourish for a very long time. However, the ratcheting up of interest in literacy and Christian values has helped to challenge this atypical social arrangement. As Christian values took root, men and women began to discern that it is their prerogative to pick and choose who they marry. Even though this obsolete practice is gradually but surely waning, in Idumuje-Ugboko, other forms of antediluvian marriage practices predate the coming of Christianity.

Types Of Marriages

In Idumuje-Ugboko, the following forms of marriage were recognised and practised, pre-Christian time:

- Wife seizure or capture

- Mbeme or betrothal (biased against girls)

- Marriage by divorce

- Widow inheritance (Igbu Na Nzo)

- Conventional marriage

Wife Seizure

As the name denotes, this is anything but a free-will marriage. It is exactly what it says – a forced marriage, in most cases, between a ‘trapped’ woman and another man, who may or may not be strangers to each other. Certain conditions have to be present for wife capture to occur. Wife capture will take place if:

- A bride rejects a marriage proposal when both parents, extended family and the Ebo have already agreed to it

- An entirely new suitor arrives on the scene and both families have a mutual interest in accepting the advances of the new suitor. If the family give the nod to the ‘meddler’ at the expense of the first suitor, wife seizure may take place with the new suitor most likely to be the instigator

- The prospective groom’s parents and the bride agree to the proposal, but the bride’s parents claim that the bride, most probably a prepubescent child, is not mature enough to be married

- A bride accepts a marriage proposal but the proposal is rejected by her parents

Were any of these circumstances to present themselves, the men from the bridegroom’s Ebo will be instructed to go and abduct the bride, either in broad daylight or during a moonlit gathering. Her capture is usually announced by gunshots by the bridegroom’s Ebo men. The instant consequence of the abduction is an (en) forced rape, actively encouraged by the older Ebo women. The loss of the bride’s virginity is a calculated act to humiliate, entrap and compel the bride to stay with her husband in order to avoid the ignominy that will follow if she rejects the marriage.

Mbeme Or Betrothal

This type of marriage is usually contracted as a result of a mutually binding promise between two families. The promise can be in lieu of a debt owed, a favour offered and taken, or to cement family ties. Chiefly, this involves marrying off a girl under the age of consent to an older man.

Irrespective of the reason for contracting such a marriage, once a girl is betrothed, the intent is cemented by the presentation of a symbolic log of wood to the girl’s family. This log of wood represents ‘warmth’, – interpreted to mean the man’s burning desire to have the girl as a future wife. Consequently, the man must continue to ‘service’ and ‘renew’ this agreement in various ways before he eventually marries the girl. The demonstrable acts of ‘continuous service’ may include but not limited to, carrying out unpaid manual work in the girl’s family farm, the fetching of water, the presentation of palm wine as a gift during festivals or the rendering of ad hoc domestic assistance at the prospective in-law’s home. At ‘maturity’, the girl’s bride price is paid. The girl, now probably a fully grown woman, is married off by her family.

Marriage by Divorce

The term ‘marriage by divorce’ is misleading both in concept and execution. Ordinarily, this union should take place at the end of a divorce proceeding. Instead, marriage by divorce in Idumuje-Ugboko culture means a marriage entered into with a woman who is already married. The game plan of the meddling groom is to wrest the woman from her current husband, mainly by inducement. The inducements may be in the form of a steady supply of palm fruits or choice farm produce, money or the gift of expensive and intricate traditional dresses. If these incentives were to fail, it is ‘acceptable’ for the man to resort to elaborate subterfuge. In extreme cases, men have been known to deploy black magic (juju). If and when the man succeeds, the woman will be left with no choice but to divorce her current husband and marry the new, perhaps, more endowed suitor.

Widow Inheritance (Igbu Na Nzo)

Widow inheritance or bride inheritance traditionally referred to as Igbu Na Nzo, is a socio-cultural practice that, most often, compels a widow to marry a male relative of her late husband, often his brother. This practice is similar to the Biblical Levirate marriage – a type of marriage in which the brother of a childless deceased man is obliged to marry his brother’s widow. Similarly, in Idumuje-Ugboko culture, if a woman marries into a family and is widowed, this dying custom permits a surviving blood brother of the late husband to ‘inherit’ the woman or execute what is traditionally referred to as Igbu na nzo. Not minding the marital status of the surviving brother, the widowed woman is constrained by this antiquated custom to accept the brother of her deceased husband as her new husband.

This sort of practice was not limited to the royal household. When the C.M.S. missionaries were stationed at Idumuje-Ugboko, Frances poignantly documented the various attempts to forcibly marry off young girls to much older, living relations of their deceased husbands. She writes:

The history of Idumuje-Ugboko is replete with nuances of widow or bride inheritance. In some of the cases, instead of getting married to the brother of the deceased, the widow is inherited by the son of the deceased. For example, following the death of his father (Amoje) Nwoko I, Omorhusi on ascending the throne inherited Onwughai his father’s wife. Onwughai later had Nwobe, and notably, Nkeze for Obi Omorhusi. Furthermore, when his father died, Nkeze inherited his father’s wife, Oyibo. Together, they had Akaba. Given the oddity and quite recently, the unpopularity of this practice, widow inheritance and its variant forms are infrequently and reluctantly practiced by fewer and fewer people and communities.

Conventional Marriage

Conventional marriage is a marriage that allows prospective couples the freedom to choose their partner and still tick all the acceptability boxes. In practice, a conventional marriage in Idumuje-Ugboko (and in most Ibo communities) does not entirely preclude (rightly or wrongly), the influence of both sets of parents or extended families in determining the suitability of a partner. Most often, there are good reasons for this sort of ‘pre-marriage interference’. This can range from unwittingly marrying into a family with an objectionable history of madness, genetic disorder, murderers, thieves, to hard-to-detect ‘generational curses’. To weed out such undesirables, each family carries out clandestine eligibility checks on the immediate, and sometimes, the extended families of the prospective in-laws. Such rigorous background checks have become culturally acceptable. Nonetheless, this practice has the unintended consequence of compromising the supposed freedom of choice. So often, a failed eligibility check is known to have scuppered marriages. Even though the decision to choose a wife or husband should rest solely with the prospective couples, some conventional marriages are anything but a freewill choice. Recently, urbanisation, literacy, Christianity, and more importantly, genetic disorder awareness is gradually eroding, blunting and systematically replacing the overbearing influence of families in determining the suitability of a couple. .

Conducting A Conventional Marriage In Idumuje-Ugboko

The Idumuje-Ugboko culture, tradition, and custom, now recognise and accept two forms of conventional marriages – a white wedding, commonly referred to as a church and/or registry wedding and traditional marriage. A white wedding or registry wedding came about with the advent of Christianity as its concept and application are styled after the Western culture. On the other hand, traditional marriage is the solemnisation of marriage according to the customs and traditions of the community.

Traditional marriage typically involves various stages of cultural rites. One important stage is commonly referred to as Ikwu aka – the initial notification of the intent to marry, or what is known as the introduction. This stage is usually initiated by the groom. The visit of the groom to the bride’s family is accompanied by the presentation of drinks and kola nuts – a traditional fruit that depicts friendship. In most Ibo cultures, it is usually at this stage, and sometimes beyond, that the extended background checks are carried out.

Once a satisfactory background check is achieved, a date is set for Igba nkwu – the presentation of drinks to the bride’s family. This involves feasting, dancing, and merry-making. Even though a marriage (be it Western or traditional) is a celebration of holy matrimony, one primordial act that gives either type of marriage ‘authenticity, credibility and cultural recognition and acceptance is the payment of a bride price – a form of payment made by a groom’s family to the bride’s family in lieu of taking their daughter as a wife.

Pre-monetisation, the payment of a bride price was either in the form of valuables, services, property, cowries, or any other form of a pre-agreed instrument between the two families. Amongst the Ibos, cowries – a group of small to large sea snails, cows, goats and even farm produce were, until recently, accepted as forms of bride price. However, as these payment media became monetised, Idumuje-Ugboko culture was not left behind. The far from crippling bride price set in Idumuje-Ugboko is usually seen as a token or a gesture of acknowledgement from a husband to show eternal gratitude to the bride’s parents. It is never a carte blanche to trade a daughter to a man and his family.

Even if one or both of the couple are based abroad, the bride price in Idumuje-Ugboko is always denominated in Naira – Nigerian currency.

The current bride price is set as follows:

- Amount to be paid to the bride’s father = ₦25,000.00

- Amount to be paid to the bride’s mother = ₦ 15,000.00

- Amount to be paid to the bride= ₦500.00

When a marriage is contracted between a non-indigene and an Idumuje-Ugboko daughter, an acceptable bride price may sometimes be ‘negotiated’. In such infrequent instances, the consensus amount is not always poles apart from what a native will normally pay.

In a conventional marriage, particularly the traditional type, there are usually a stipulated quantity and a specific brand of drink which the groom’s family must present to the bride’s family and the Ebo. These gifts are a prerequisite for completing the marriage process. Once these obligatory conditions are met, prayers are offered by the Ebo elders. This stage is always accompanied by dancing and feasting. Once every element of the marriage is concluded to the satisfaction of both parties, the groom, if he so wishes, is now in a position to take his bride home, but not before he is obliged to pay an escort fee of ₦2,000.00, together with a bottle of spirit. If for any reason the bride is unable to go home with the groom the same day, the bride’s parents MUST inform the groom’s family when the wife will be joining the husband. On the agreed day, the bride must be accompanied by escorts who, in turn, must collect the mandatory escort fee before departing the groom’s home.

Maintaining a Family Name

The act of maintaining a family name is a cultural requirement that immoderately places a higher premium on having a male offspring over a female offspring. This is known as Androcentrism – the practice, conscious or otherwise, of placing a male human being, or a masculine point of view at the centre of one’s worldview, culture, and history. In Idumuje-Ugboko, it is viewed with disapproval for a family, referred to as an Ezi (meaning, compound or home) to be without a male child. According to this tradition, it is a male child who maintains the name of a family. In reality, even though this practice is overvalued, it can, in certain situations, be remorselessly and unrelentingly enforced.

When a marriage is not blessed with a male child, that marriage is wrongly seen and judged as ‘unfulfilled’. Usually, in such instances, certain measures are put in place to ensure that the family or the Ezi does not become ‘extinct’, or to put it in the traditional context, the compound is not ‘closed down’. For example, if a man dies without a male child and the wife is still within her reproductive years, the husband’s Ebo will encourage and, ever so often, aggressively urge the woman to ‘go out’ and procreate in order to preserve the name of her late husband. At the other end of the spectrum, if the woman is past her reproductive years but has daughters, the Ebo will coerce one of the daughters, usually the eldest to swear a binding oath, promising:

- Not to marry

- To get pregnant and bear children, at least a male child

- To meet the two conditions above before getting the ‘freedom’ to marry if she so wishes

However, if the daughter is unable to bear a son, or ends up having a female child or daughters, when she dies, she will not be buried until her own daughters agree to take an oath, pledging that ALL the children they will give birth to must belong to the Ebo and their grandfather.

Birth

Before cottage hospitals and primary healthcare became widely available, almost all childbirths were carried out under the general supervision of traditional medicine women who doubled up as midwives. In fact, some unplanned deliveries happened in inauspicious places like farmlands or streams. Irrespective of where a baby is delivered, any addition to the family is always greeted with joy, fanfare and revelry.

At the birth of a child, and before a woman enters her house, water is poured on the roof and allowed to cascade on the new mum. For the new mother, this ritual is a symbolic cleansing act. Once the baby is ensconced in a nursery, and depending on the Ebo, five or eight tubers of yam are placed beside the child. This act is quite instructive because the placing of the tubers of yam is a traditional way of counting down to the naming ceremony, or what, in the Western culture is referred to as Christening. From the day the tubers of yam are placed beside the child, a meal preparation requires the family to take one tuber of yam every day until the last tuber is consumed. The consumption of the fifth or the eighth tuber of yam is a signal to name the child on that very day. The naming ceremony usually attracts friends, extended families and well-wishers who join the family in dance and festivity.

Death And Burial

The handling of the dead including post-internment is one of the most rigid and prescriptive ordinances in most Ibo culture. In Idumuje-Ugboko, most deaths and the burial rites that follow involve strict adherence to specific custom, rules, and immutable procedures. For example, the simple act of announcing a death can be bizarrely fetishised. In time-honoured tradition, euphemism is routinely used to announce the death of a person. The reason for this is partly to do with the unalloyed belief in life after death. To announce a death, a gathering of the Ebo is informed that one of their own is sick. In line with this outlandish custom, a ‘curative’ medicine is mandated to be prepared for the sick person. This manner of presentation is usually a trigger to deploy in auto mode the various burial mechanisms, only slightly affected by other equally peculiar customs, as every burial rite is not always the same.

In Idumuje-Ugboko, there are two types of burial rites – an Ogbe (village) and an Idumu (quarter) burial rites. Since certain customs cannot be ignored, it is usually the village elders who determine the appropriate burial rites to be accorded a deceased. For instance, the age of the deceased, the conferment of a title or lack of one will determine the type of burial rites to be observed. An old man or woman who holds a traditional title will attract an Ogbe burial rite, while a young man, even if he was titled, will be honoured with an Idumu burial. In exceptional circumstances, the burial arrangements for a titled, old man can be judged as an Idumu affair if the children or the relations of the deceased cannot absorb the sometimes prohibitive cost of the burial. Either way, according to the custom, an older living relation of a deceased is not permitted to actively engage in a younger person’s internment.

There are marked differences between an Ogbe or Idumu burial. The most conspicuous difference is the involvement of the Ikolos. When a burial is an Ogbe affair, the village Ikolos will be involved, while an Idumu burial attracts only the Idumu Ikolos. Another notable difference is the burial cost. In an Ogbe burial, for example, the cost is evidently higher than an Idumu burial. The Idumu burial rite is, in practice, a no-frills burial.

Once the type of burial is determined, the Ebo elders will begin the practical application of the ‘curative’ medicine. The putative medicine is no more than making concrete arrangements which involves sourcing the following items:

- The casket

- Chicken teeth

- Three white pieces of (wool) fabric

- A he-goat

- Dog horn

The procurement of these items is a signal to start bolting down the concomitant logistics, like the handpicking of the pallbearers, the identification of the burial site and the activation of other traditional rituals.

Disregarding the type of burial to be undertaken, certain customs remain constant. One very important custom is the wake. An important group that play a pivotal role at this stage is the Umuada – the Ebo women – whether married or single. For a widow, the Umuada are the permanent fixtures that keep the widow company throughout the night, and often, for the duration of the burial and the traditional rites that follow.

Upon committing the deceased to mother earth and the grave covered, the entertainment of extended families, friends and well-wishers will usually follow. Specifically, the entertainment of the Ebo or what is traditionally called Ine Ebo is an important element of the post-interment rites. This is when the family of the deceased provide food and drinks for the Ebo. The extravagance or the thriftiness of the occasion is dictated by the financial strength of the bereaved family.

One element of the burial rite that was so pronounced before the coming of the missionaries but has been in steady decline in both appeal and practice, is a second burial. Pre-Christian period, a second burial particularly for the old or persons of high standing in the society was not only mandatory, it was always elaborate, colourful and accompanied by frenzied fanfare and merriment. Typically, this involves exhuming a corpse after four or five months and reinterring it deep inside the ground, but this time inside the house of the deceased. For example, a description of what happens during a second burial and what awaited a pre-convert like Onwadiebo when his father Chief Ogwu, the Iyase of Idumuje-Ugboko dies was vividly captured by Frances Hensley. She writes:

–Frances Hensley

Furthermore, when Nwabuoke of the royal family died in Asaba prison on Sunday, June 14, 1903, the event surrounding his second burial was tellingly mentioned during one of her itinerations. She writes:

… You will be glad to know that I have Odega [Paul Odega Monye] in my train. He waited to come because they are beginning the second burial for Nwabuoke and it is very difficult for him being in the same house.

–Frances Hensley

The Place And The Role Of Shrines In Idumuje-Ugboko Culture

In many African cultures, the word ‘shrine’ evokes a morbid fear of spirits and the paranormal. To people unfamiliar with the African culture, the mere mention of the word shrine can induce different feelings ranging from heathen, nasty to downright evil. However, to majority of traditionalist Africans who are undoubtedly theists, shrines are revered and regarded as the home of the gods and the goddesses, whose boundless and mystical powers to control both the here and the afterlife are real and legendary. As a result of this entrenched understanding, different shrines and deities are fervently celebrated in dance, feast, and libation. Sometimes, the act of psychomancy that uses an arcane language is initiated. In Idumuje-Ugboko, Polytheism – the worship of, and the belief in multiple deities are widely practiced. Shrines are seen as a place of sanctuary by worshipers and believers. Both parties hold an unwavering belief in the efficacy of their powers.

A good example of how highly the community rates the potency of the shrines was aptly captured by Frances Hensley in one of her letters. It reads:

In most traditional African societies, the shrines to guide and guard the inhabitants of a new settlement are always erected the same time the settlement is established. Also, when worshipers embark on journeys (both far and near), the shrines are usually consulted to ask for protection and journey mercies. There are prescriptive items the custodians of these shrines enjoin the worshipers to bring with them when they want to consult the gods. The inexhaustive items may include a cockerel, a goat, a ram, kola nut, palm wine and food. Also, depending on the reason for the consultation, different types of sacrifices are offered. Sadly, in some Ibo cultures, this sometimes may involve the unconscionable act of a human sacrifice.

To the worshipers, these shrines represent a Pre-Christian way of worship and belief system. It also represents the centrepiece of the community’s unity. In unique circumstances, shrines can also act as a source of arbitration – a traditional legal system of some sort. In extraordinary circumstances, these shrines are used for fiendish purposes, either to harm or ‘destroy’ someone. When used in this manner by either the custodians, the worshipers or both, the sole purpose is an odious display of the supposed ‘strength’ and the blatant wickedness they purport to possess.

Post-Christianity, the ‘protective powers’ and the implicit belief in these deities was challenged by the missionaries. This caused several conflicts between the traditionalist on one hand and on the other hand, the Christian converts, the missionaries and the colonial government. The incandescent anger felt by the traditionalists was directed at the missionaries. They were patently unhappy with the challenge to their authority, their source of power and livelihood. The attempt by the missionaries and the colonial government to double down and change some of these hidebound cultures and traditions resulted in many face-offs. In extreme situations, the use of violence or outright war was instigated. For example, the incompatibility of these two religious systems, beliefs and values resulted in a game-changing conflict that had a profound effect on the town of Idumuje-Ugboko. A direct consequence was the Ekumekwu war which effectively ended the C.M.S. activities in Idumuje-Ugboko.

The four villages and the twenty-four quarters in Idumuje-Ugboko have their fair share of shrines. A few of the shrines in the four villages will be looked at.

The Ogbe-Obi Shrines

The Ozala shrine of Ogbe-Obi belongs to Idumu-Ugo. The provenance of this shrine is a lady called Ozala, the wife of Nwonye – hence the name – Ozala Nwonye. It is located along the farm road of Idumu-Ugo and Owu.

Mkpitime is a shrine located in Idumu Isagbeme. The Uzebu and the Owu quarters have their respective shrines.

The Onicha-Ukwu Shrines

The Ohai shrine of Idumu-Ukwu is one of the most important shrines in Onicha-Ukwu. The advent of Christianity has diminished the importance and the worship of this shrine.

The Ogbe-Ofu Shrines

The Ihu Ohai, Idigwu (the god of iron) and Iyor (the stream god) are shrines located in Idumu Anya. If anyone is suspected of witchcraft, the individual is made to swear at the shrine to prove their innocence or guilt. The Ohai shrine is renowned for healing and purification. The Iyor shrine forbids any sexual acts during the day.

The Atuma Shrines

Idumu Onije has Ohite (a shortened form of Ohai-Te) as their shrine. It is claimed that the god associated with this shrine induces mental illness. Other shrines found in Atuma are Ozala (in Idumu Ona), Ovie and Ake (in Idumu Ezi).